How Work Became a Cult

We all have utopian dreams of a world without mandatory work, but we’ll never let ourselves achieve it

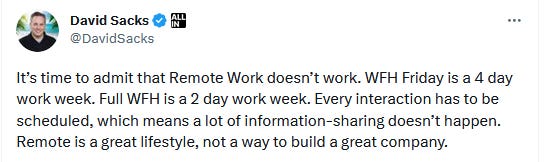

David Sacks, the venture capitalist and sniveling Igor to Elon Musk’s Frankenstein, recently forgot he’s not the boss of everyone and told us all to get back to the office, declaring remote work a failed experiment.

His thinking is that remote work isn’t actually work at all, and a day of working from home is really a day off work. That’s not an argument he makes, per se, it’s just a conflation he’s already made in his own head and assumes we have too. Throughout the entire Twitter thread he’s referring to work from home days as days off and laments that we, in our drive toward laziness, have fallen into a fewer-than-five-day work week.

There are multiple problems with this and my brain is immediately faced with the challenge of where to begin. I got to thinking about the nature of work and think, even if working from home was the productivity equivalent of taking a day off, what would fundamentally be wrong with working a little less?

It’s not the threat of the world falling apart. A lot of us could take a lot more time off if we wanted to without anything fundamentally breaking. But the very nature of our society is that it’s not structured in a way that allows us to do that. People like David Sacks and other capital-c Capitalists don’t want it to be.

There is a reason why the universe of Star Trek is one of the most popular franchise universes in the history of science fiction. It asks us to imagine a future free of unnecessary obligations, where magical technologies like matter replicators have made toil and grind a relic of the past. Citizens of this universe are post-scarcity—work is optional and heavily specialised, the domain of those who really are driven by the love of their pursuit and their mission.

People believe that this sort of utopian world is one of the end goals of human civilisation. Even the great economist John Maynard Keynes predicted in his time that the work week would reduce and soon would be down to just 15 hours. But that is to misunderstand the trajectory of human civilisation. We’re no more traveling toward a post-scarcity world than we can land on the moon by diving deep enough underwater. Artificial scarcity is a built-in feature of our economy—where we don’t have scarcity as a matter of fact, we manufacture it.

In our wisdom we have created an entire economic system based almost wholly on resentment. A crab bucket economy. The overarching philosophy that people should only be permitted to have the life that they worked to deserve. The reasoning behind this philosophy is simple—your ancestors worked hard to dig themselves up from nothing. It is your responsibility to do the same. A philosophy that both acknowledges that your life is easier in a lot of ways than that of your parents, and firmly chastises those who seek to take advantage of that fact. You’re failing to pay back a debt, in essence, stealing.

Just interrupting to let you know the vast majority of what I publish is free, but if you wanna upgrade to a paid subscription for just $5 a month ($50 for a year—cheaper!!), not only do you help me continue doing what I love, but you get every article a whole week earlier than everyone else.

Don’t want to subscribe via Substack? A Ghost version is also available for paid subscriptions only.

It's a philosophy that appears noble but is also unsustainable in a world where both work efficiency and population are in infinite growth.

The idea of the average person living a marginally less stressful and less laborious life drives folks into a frenzy of outrage. It was the same moral outrage that was triggered by the US President’s recent decision to relieve student debt—the absurdity of which was captured in a now famous tweet by TV writer and cancer survivor Aaron Fullerton.

There is no practical reason why young people these days should be saddled with such enormous debt besides the fact that it isn’t fair to past generations if they’re not. It’s not really about the potential for raising taxes if debts are unpaid, even if that’s the ribbon and bow the complainers dress it up with. The controversy is over education itself. It’s not Work.

There are reasons why conservatives despise tertiary education and speak of virtually all of it with venomous ridicule.

Your grandpa didn’t go to school and read books, he worked 20 hours a day in a canning factory. Why aren’t you? We don’t even treat the nature of the work as being particularly relevant, as long as it’s work. We don’t treat work’s primary function as being necessary for the operation of society. We treat it as a rite. We treat it as schadenfreude. There are rules surrounding work: Primarily, it’s supposed to encompass your whole life, or the vast majority of it, and you’re not supposed to enjoy it. Work you enjoy doesn’t count.

And that’s the real drive behind the capitalist’s hatred of remote work. It’s not the risk that you’re being less productive—studies are inconclusive about the overall productivity impact of remote work, and even lean towards it being more productive—but it’s the risk that you might be enjoying it more. Or at least hating it less.

That’s not part of the plan.

Elon Musk is, of course, the absolute reigning champion of the work cult philosophy. Musk, who recently declared in his own words that work from home is morally wrong, and didn’t mince words too much that it’s because he’s bothered by the fact that he can’t visually confirm that you’re miserable. One of the first things he did when he took over Twitter was dispose of all of the office perks, and that wasn’t just the ping pong table and the comfortable chairs—he took away the toilet paper.

His vision of work both embodies the ideal of the work cult philosophy and unmasks the fiction of it. After all, his employees are encouraged to actually sleep at the office, which, in a perverse but legitimate way, is a work from home situation. One that is acceptable because it eliminates the unacceptable component—the risk of enjoying yourself.

As a society we have a terrible habit of equating relaxation, enjoyment, even just simple lack of stress, with laziness, and laziness is the sin of all sins. It’s the mentality behind hustle culture, the shame of taking a minute: If you’re not working right now, why not? What are you running away from? What is wrong with you? You’re disgusting. It expresses shame in even indulging in the benefits of hard work that are ostensibly the reason for engaging in it in the first place.

While I was writing this piece, quite by chance, I stumbled on the most hilariously on-the-nose example of what I was trying to express, and I’m kind of miffed that someone actually said it outright, validating though it may be. Here I was searching Twitter for something else entirely when this popped up in my feed:

It is exactly what it says on the can, and it’s not written with any irony. A lot, of course, has already been said about the bizarre ways in which many Christian conservatives try to reconcile the love of Christ with their own vicious hatred of charity and welfare. Here, venture capitalist and prosperity gospel style preacher Lance Wallnau tries to lay out the Biblical case for why the unemployed should die, preferably painfully, and maybe on fire.

He goes on to reiterate why enjoyable work doesn’t count, why work should be miserable and above all mandatory. His argument drives from the same principles of self-flagellation and divine punishment that also supposedly explains why childbirth has to be painful:

This is explicitly a religious argument, yes, but, like all religious arguments that throw out the teachings of Christ to try to shoehorn hustle culture into the Bible, the religious argument is just a convenient cherry-pick to reaffirm the beliefs that Wallnau has already settled upon—the same beliefs shared by all the work-cult leaders: Every second you’re not working, every second you’re not grinding, is a moral slight against anyone who ever worked harder than you.

It's the mentality that is defeating us as a species. And it is going to come to a head before too long, I think, because there’s a limit to how much we can artificially hold back technological advancements that will eliminate the need for a large amount of the work that we obsessively do? Self-driving vehicles are coming, for example, and human drivers form one of the backbones of industry. AI now has a gun to the heads of many key occupations as well. Capitalism has no contingency plan for this. Or rather, Lance Wallnau’s “let them die in the street” philosophy is the contingency plan. So what will happen to us when our own technology forces us to all confront our culture of resentment?

What will happen when we’re all forced to relax?

My husband works way harder at home. People who can't do their jobs from home resent that he's able to. He'll go in on a day he has nothing much to do just because he automatically looks like he's doing more work just by being in the office, even if all he does is wander around and talk to people. He gets so much more work done at home because his coworkers aren't constantly pulling him away to put out their fires. And yet at home he's stressed about making up a 15 minute break (BTW he's on salary! But he has to track his time for project budget purposes I guess?) because it'll look bad. They don't monitor him but if he's not answering his email fast enough or churning out enough work, that looks bad.

It makes be really glad I can just go in, make pizza, help my co-workers, do dishes, and go home at the end of the day feeling like I accomplished something and did my share. My biggest source of stress in my office jobs was "looking busy" even if my boss knew I had no work to do.

PETER

Well, I generally come in at least fifteen minutes late. I use the side

door, that way Lumbergh can't see me. Uh, and after that, I just sorta

space out for about an hour.

BOB PORTER

Space out?

PETER

Yeah. I just stare at my desk but it looks like I'm working. I do that

for probably another hour after lunch too. I'd probably, say, in a

given week, I probably do about fifteen minutes of real, actual work.