The Ontology of Twilight

He's right, you know. I'm not Sergeant Lincoln Osiris. Nor am I Father O'Malley. Or Neil Armstrong. I... I think I might be nobody. -- Kirk Lazarus, Tropic Thunder

I don't read tabloid gossip magazines, okay? I just walk past the news agency and glance at the headlines. That's something interesting about our modern society, so immersed in celebrity culture that you can't walk down the street without knowing whether Kirsten Dunst wore a baggy sweater the other day and some people are wondering about whether maybe it's a baby bump. That's the deal that you sign when you become a famous person - money, adoration and eternal life, in exchange for never having a single moment of privacy ever again, because the common people need somebody to live vicariously through. It's my theory that we don't actually love celebrities - we despise them, because we're not them. Who we think we love is the fiction that we build around them, a fiction we can get inside, so that we can actually wear their skin like some kind of metaphorical Buffalo Bill.

I came up with an interesting ontological idea about actors. Well, everybody really, but actors most notably. People are all actors, to a point. There is an inner reality, somewhere deep inside, our true selves if you will. Then there is the outer shell, the person we project onto the world, kind of the mask that we wear when we walk around among other people. That's the character that we play, and everyone has one, because sometimes we don't like something about that person deep inside and because we're imaginative beings we're able to construct, and play the part of, the person we really wish we were.

Actors are interesting because they have this extra layer on top of it all, the character that they are really playing on stage or screen, but unlike their private character, they want you to know that this character is fiction. That's the social contract that we sign when we participate in fiction - a story is literally a lie, but one that we temporarily agree to pretend is true. But sometimes, I think, this contract can get smudged, and an interesting phenomenon occurs when all these different characters get muddied up together...

Too much? Sorry about that. Let's back up a bit. I want to talk about Twilight.

There's this series of books you may have heard about, but maybe not, they're pretty obscure. It's a story for teen girls that got popular because it's basically engineered to push all the right buttons. The protagonist, Bella, is essentially a manifestation of the character that a lot of girls want to be. She's almost flawless, her biggest problems in life being that she's just too pretty and too popular, with all the complications that come with being both really smart and really beautiful. One day, she meets this guy, who just so happens to be the perfect boyfriend. He's also a vampire. His character traits include being completely loyal to her, being crazy psychotic but never inclined to turn his anger against her, while at the same time, willing to talk about his feelings and hear about hers.

Later, she meets this other dude. He's basically the same character except that he's rugged and outdoorsy, has a rock hard sixpack, and the ability to transform into a wolf. He's also the perfect boyfriend, and also falls for her. Naturally, werewolf and vampire don't get along with each other, and it's not just because modern culture has invented this idea over the last decade or so that vampires and werewolves are sworn natural enemies. Beyond the fact that they're monsters, they develop a macho rivalry against one another, and poor Bella is faced with the problem that all teen girls must face at one stage or another - will she hook up with the tall, brooding, handsome, mysterious guy? Or with the rugged, masculine bucket of sex?

People got obsessed with these books to the point of psychosis. If there's one thing Stephenie Meyer got absolutely spot on, it's the secret fantasy of the average white heterosexual middle-class teenage girl. Then the movies came out, and that's when things started to get strange.

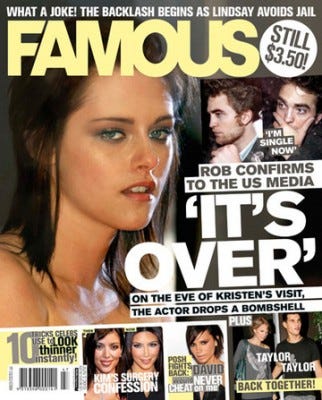

This is Kristen Stewart. She's an actress by trade, and let's face it, we don't know much about her, because we don't know her. A lot of people think they know her, though, because of the various masks that lie on top of whatever reality might exist. In our withdrawn third-hand account of Kristen Stewart, this is what we think we have sorted out: She's your average teenage girl, adored by everyone, whose biggest problem in life is deciding between two men. Robert Pattinson, completely loyal and genuine and caring but by all accounts a total psycho, and Taylor Lautner, a rugged, masculine bucket of sex.

I know what you're thinking about me right now - the observation that tabloid gossip magazines make up all their "news" is neither original nor interesting. I might as well suggest that water is wet. Still, I think there's something particularly interesting about this one case, and maybe something, dare I say, philosophically significant. That's this: People are actually confusing the actors in the Twilight films with the characters they are portraying. Whether it stems from an extraordinarily powerful desire for Twilight to be really real, or just a simple processing error in the brains of diehard fans, the tabloid narrative of Kristen Stewart's life almost matches that of her character, Bella. She falls for Pattinson, he dumps her, she runs into the arms of Lautner, then she dumps him when Pattinson shows interest again. Then she gets knocked up.

This gets back to the ontology of film actors, and why it's complicated. We're not looking at two layers of reality, here, but four. The actual story of Twilight, the story that the fans make up, the story that the actors project, and the truth. Now, if I really want to get trippy and risk accusations of hitting the bong too hard, I could point out that someone like David Hume would deny that the deepest layer exists at all. That it's really fiction all the way down. Of course, Hume could never imagine a world in which we instantly know all the details of someone's life from the other side of the globe, but he would definitely point out that those details are always necessarily fictional.

So, which fiction is better? What can we say is true about Kristen Stewart? The one we made up, or the one she makes up? Maybe the fans should just submit to their desires and actually believe that Twilight is real. Why not? Some of them probably do already. And if everything is fictional already, then it's hard to pinpoint exactly what's wrong with that.

Am I thinking too much into it? Absolutely. That's part of the fun. If I was to get back to pragmatism and speculate on the truth beneath the fiction, it would probably look something like this: At the risk of being crude, of course they're all fucking.

They're all attractive young people, and their job, literally what they're paid to do, is to generate sexual tension for the duration of four big budget Hollywood films. They're flirting, cuddling, smooching and dry-humping each other, probably for thirty takes in every scene of every film. The most shocking revelation would be to find out that they didn't spend their few off-set hours relieving hormonal tensions frantically in the back of someone's trailer. And that's just another example of fictions melting into one another. Making movies has an interesting psychological effect on actors. That's what supposedly killed Heath Ledger - when you're forced to literally adopt a new personality for months at a time, you can start to forget what's real.

Ever noticed that actors who play couples in films often wind up married a few months later? Then they divorce a year after that? The unnatural state that they inhabit, having a relationship essentially forced upon them, creates some kind of temporary confusion. Some actors are repeat offenders, dumping each spouse as a new role comes along and they get hung up on the fiction again and again. But then, to what point can I say that any of these relationships are really fictional? Maybe the fiction goes all the way down.